6 Patterns for Building Workflow AI Agents

I spent the last two months building an AI agent. Here are the 6 top patterns that I learnt from my experience.

For the past two months, I have been building an AI agent using the Claude Agent SDK to make short-form vertical videos.

The agent handles everything from sourcing content to generating scripts, adding B-roll, selecting music, and composing the final videos.

Here are the 6 patterns that I learned from building this agent.

1. Decompose Work with Sub-Agents and Skills

I started off with one agent that did everything. It quickly became clear that the agent was trying to do too much at once. While the key was to break down its work, the best way to do so was not immediately obvious.

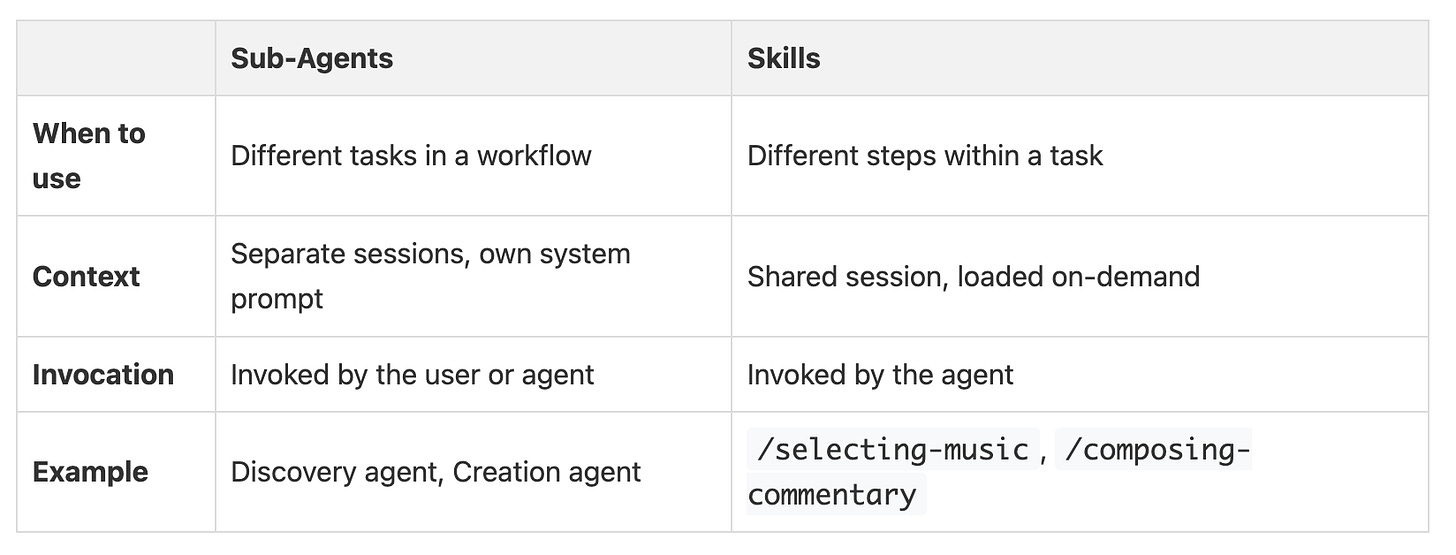

I tried separate agents, sub-agents, and skills. Ultimately, I found it useful to think about decomposition in two ways: sub-agents and skills.

I use sub-agents for completely different tasks within a larger workflow. For my project, this meant having one agent for discovering content and another for creating the video. Each sub-agent has its own system prompt and runs in a separate session.

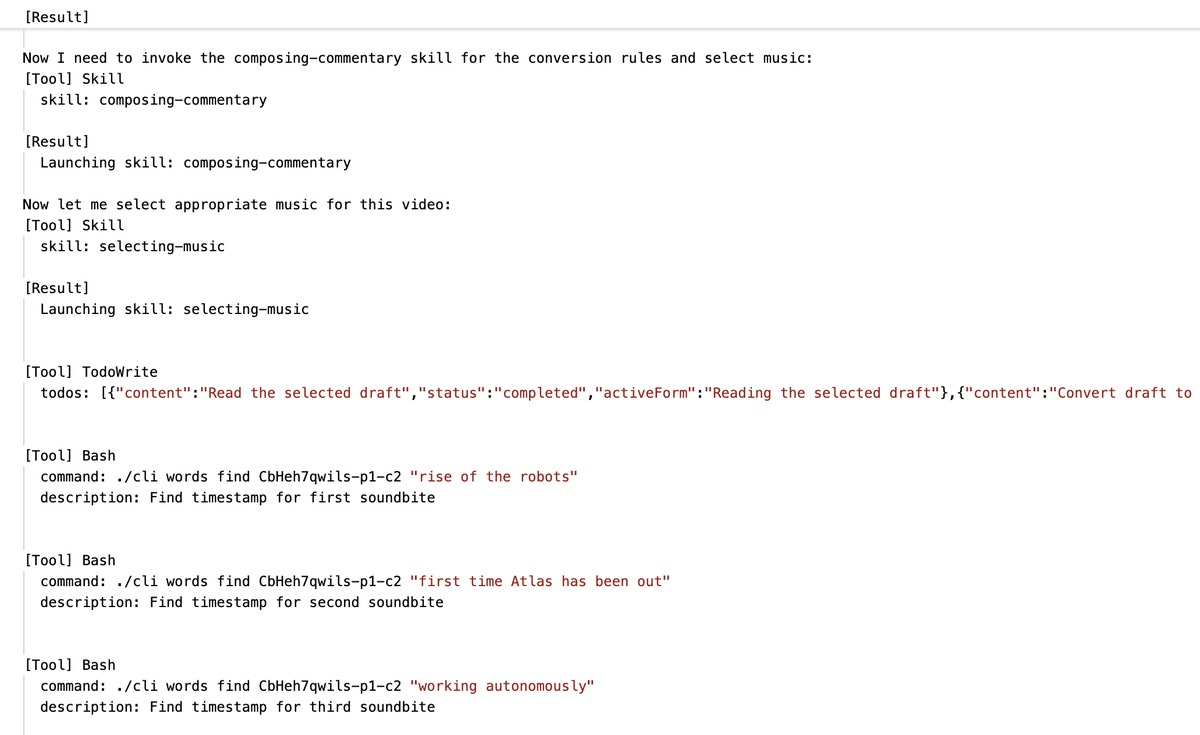

For smaller steps within a single task, I use skills. My video creation agent uses skills like /selecting-broll to find footage or /selecting-music to choose audio. These skills are loaded only when needed and share the context with the main agent.

Like prompts, skills can be composed from parts or dynamically generated before agent invocation. This is helpful if you want to dynamically adjust the skills based on some kind of catalog or knowledge base.

2. CLI as a Universal Interface

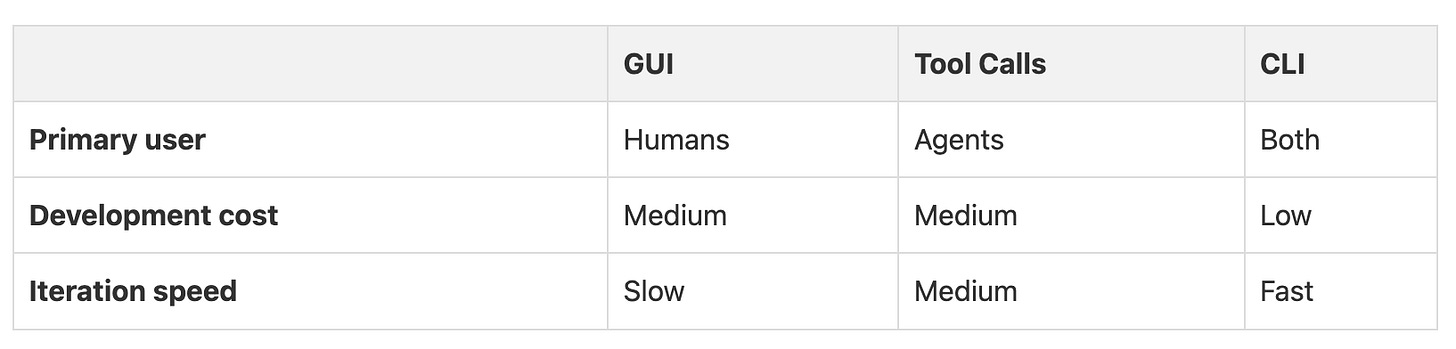

I decided to skip building a graphical user interface (GUI) for my agent at the beginning of the project, based on my previous experience of spending too much time on GUI development.

A traditional approach, which involves a GUI for humans, and separate tools for agents, doubles the development work. I built a command-line interface (CLI) instead. This single interface could be used by both me and the agent, making development much faster and debugging far easier.

When my agent ran into an issue, I could reproduce it by running the exact same command it used, like ./cli compose. This removed the guesswork of whether the agent’s tool call was different from a human’s action. A single CLI served as the universal interface for everyone.

You can also expose different LLM models as CLI commands for various specialized tasks. For example, I use Gemini 2.5 Pro as the underlying model for the review-video command as it is better at analyzing videos than other models.

After the agent baseline stabilized, I then added a GUI for human-in-the-loop tasks like reviewing drafts and making fine-grained adjustments.

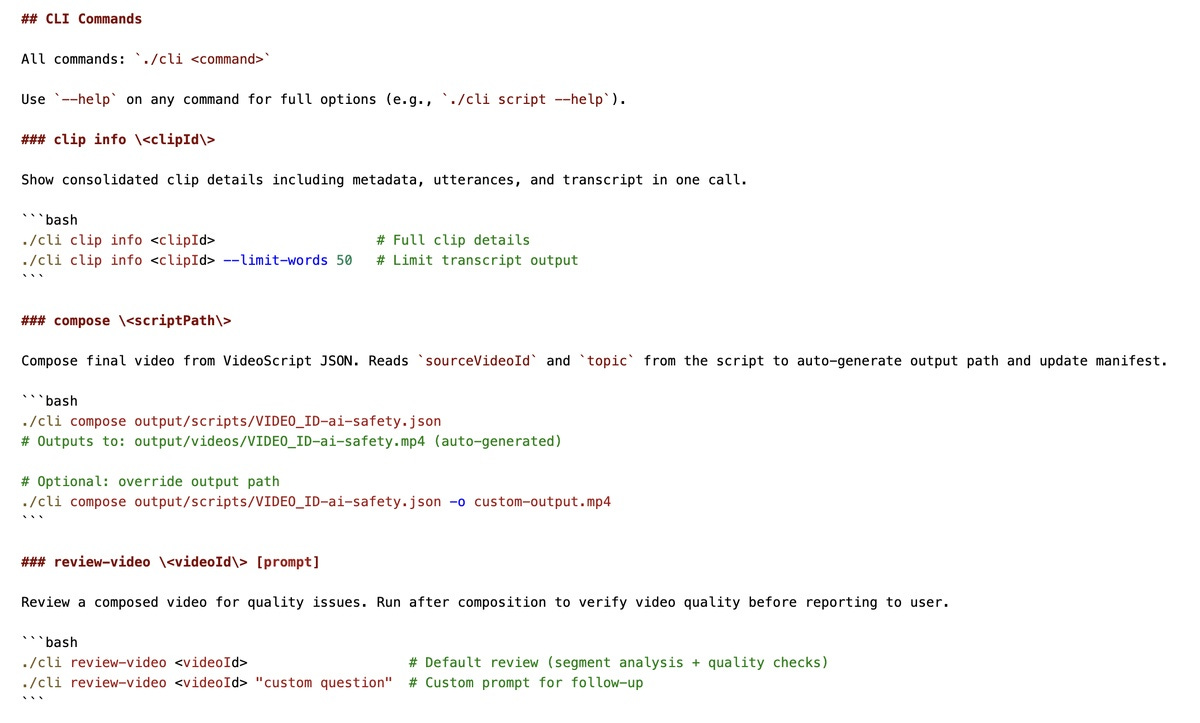

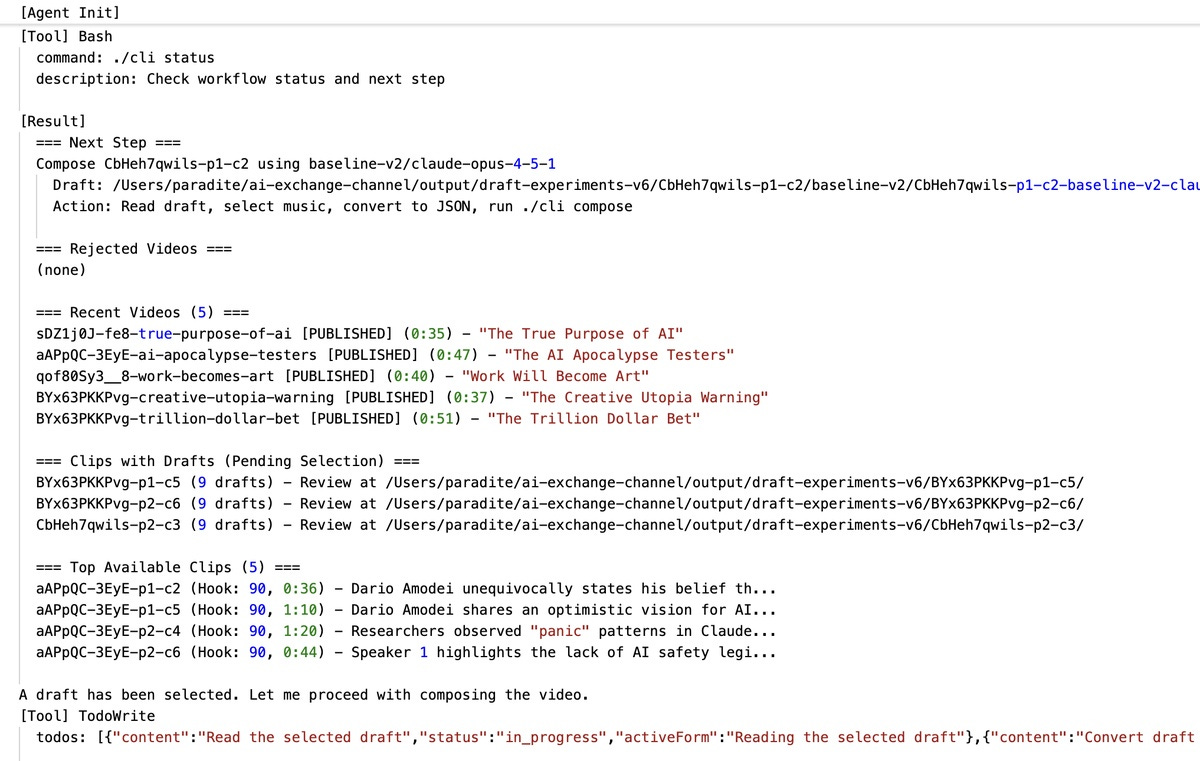

3. Guide Agents with a Status Command

Another important decision was how the agent decided what to do next. From my previous experience, isolated stages in the workflow with their own context can lead to missing context in later stages and make it hard to revise work from previous stages. I tried to let the agent figure out priorities on its own, but this led to unpredictable behavior.

The solution was a dedicated status command that guides the agent to the next action. By having the agent call status, execute the action, and then call status again, we are embedding a predictable state machine within the agent loop. The command’s output centralizes all the priority and workflow logic.

The status command outputs Next Step instructions following this priority:

1. Fix rejected video: if any rejected videos exist

2. Compose: if a clip has drafts with a human pick

3. Awaiting selection: if drafts exist but no human pick yet

4. Generate drafts: if available clips have no drafts

Now, the agent can proactively look at the status and decide what to do next, while also being flexible to whatever workflow the user wants to run via custom prompts.

4. Accept the Natural Variance of Models

I thought I could get consistent output from an LLM by refining my prompts, but it didn’t work. After weeks of trying to fix the last 15% of issues, I decided to measure the model’s variance. I ran the same prompt on the same input 10 times and found the results varied between a 76% and 88% success rate.

This shows that there is a natural ceiling for consistency with current LLMs. So I stopped chasing perfection and embraced this natural variance.

I started designing the system to work with this variance by generating multiple options (with varied prompts and parameters) and adding a human selection process to pick the best one. I had the evaluation system first pick a few promising candidates, and then I selected the best one for the next step.

5. Hybrid Validation with Code and LLM

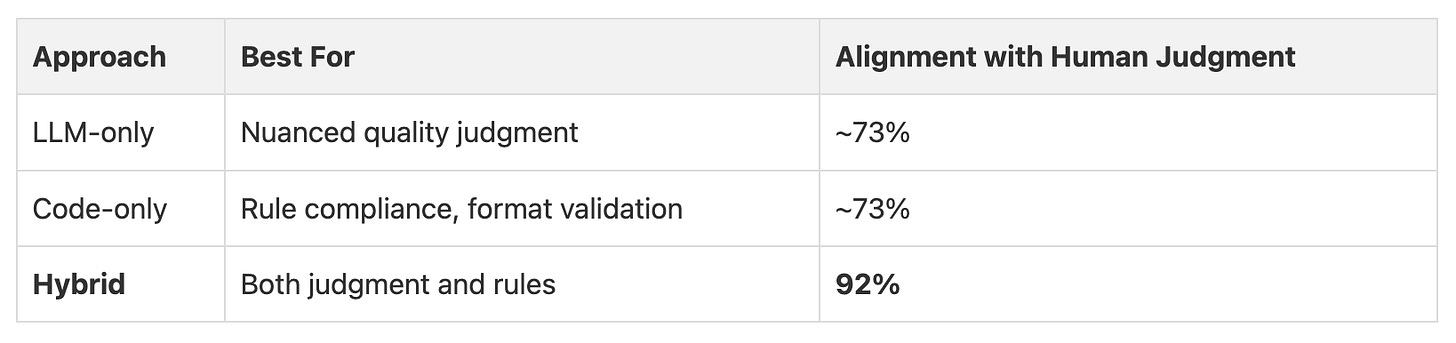

Evaluating the output of the agent and aligning it with human preference was tricky. It took me a while to get it right. The biggest improvement in quality came when I combined LLMs with simple code during the evaluation process.

I found it was better to use the LLM for nuanced judgments and use code to enforce hard rules, and then use a weighted sum to calculate the final score. This brought the alignment with human judgment from 73% to 92%.

6. Read the Logs

Recording and reading the agent’s logs was a highly effective way to improve the agent performance. Reading about the steps that the agent took, especially when it failed, revealed problems I would not have discovered otherwise.

For example, the logs showed me that my agent was trying to compose a video three times before succeeding. The issue was an FFmpeg error that happened when too many video overlays were used. So I added a validation step to prevent this from happening again.

The logs also helped me find smaller inefficiencies, like the agent calling music list when the data was already in its context. Reading the logs regularly became a core part of my development process. It is the best way to understand what your agent is actually doing.

That’s it! If you are building workflow agents, I hope these patterns provide some inspiration and ideas.

Not all of them are relevant for all use cases. And some of these might become outdated in a few months. Remember that it is important to experiment, iterate, and learn from your own experiences.